Belfast born artist John Lavery married Kathleen McDermott in 1889. Shortly after the birth of their daughter Eileen she died of tuberculosis early in 1891. In September 1903 while painting on the beach at Peg Meil in France he was introduced to Hazel Martyn, a 17-year-old who was accompanied by her mother and sister. Hazel fell in love with Lavery but her mother didn’t see him as a suitable partner since he was “a mere artist” – the Martyns were from Chicago and extremely wealthy – and was more than twice her age. She whisked her away to Paris and contacted Dr Pierre Trudeau a young New York doctor who was an admirer. Three days after Christmas they were married. They had barely settled into their apartment in Park Lane when Trudeau developed pneumonia and died leaving Hazel to give birth to their daughter the following October. Clandestine contact between Lavery and Hazel resumed and when she returned to Europe in July 1905 to the health spa at Malvern Wells he visited her and painted her portrait as “A Woman in Black.” Her mother was still opposed to the friendship and insisted on a six month separation. She brought Hazel to Rome and was delighted when she fell for a secretary at the US Embassy named Leonard Thomas. A second marriage was quickly arranged but Thomas jilted Hazel.

Lavery and Hazel married in 1908 at Brompton Oratory in London and she moved into his home at 5 Cromwell Place, a fashionable district in South Kensington. She became one of the most talked about hostesses in London. Here they entertained many of the leading figures in London including Prime Minister Herbert Asquith, George Bernard Shaw, Winston Churchill (Hazel taught him how to paint), TP O’Connor and Shane Leslie. She was regarded as one of the most beautiful women in London. In 1913 she was introduced to a group of Irishmen who lived in that part of London including Belfast born poet Joseph Campbell, Sam Maguire, Padraic O’Connor and Michael Collins. They were frequent visitors at parties at 5 Cromwell Place.

The Lavery’s were shocked by the events of Easter 1916. They did not agree with the actions of the Rebels but it awakened their interest in acquiring social justice for Ireland and in their own way set out to bring reconciliation between Protestant Unionist and Catholic Nationalist. Lord Justice Darling commissioned John Lavery to paint the trial of Roger Casement. Hazel attended the trial every day and was greatly affected by it. In his memoirs Lavery states that Hazel asked him why he did not do something for his country. He replied,”I cannot see that I can do anything without mixing myself with religion or politics and I have no time to differ with people.” “Don’t differ,” she replied, “Just agree with them all as you do anyway.” It was then he painted the triptych for St Patrick’s Church and then to show the other side “that I wasn’t a bigot” he presented the Belfast Corporation with a study for “The King, The Queen, The Prince of Wales, and The Princess Mary.” He then went to Dublin to paint portraits of John Redmond and Edward Carson having got their agreement that their pictures would hang side by side in the National Portrait Gallery. When Carson saw them he quipped, “Ah, Its easy to see which side you are on.” Redmond said, “I always had an idea that Carson and I would be hanged side by side in Dublin.” Later he painted another portrait of Carson to be hung in Belfast. Carson remarked, “Ah, Carson after the surrender.” He then painted both Catholic and Church of Ireland Archbishops of Armagh, the Grand Master of the Orange Order, Joe Devlin, Archbishop MacRory and Bishop Grierson and many others. For his efforts he was given a knighthood by Lloyd George’s government in the same week in which the Black and Tans were unleashed in Ireland. When Lavery told Winston Churchill that he was going to Ireland to paint Michael Collins (at Hazel’s prompting) Churchill advised him, “Be careful, my dear John, our men are not all good shots.” He didn’t go.

When the Irish delegation arrived in London for the Treaty negotiations in October 1921, Hazel Lavery got in contact with Hannah Collins and Michael Collins duly arrived at 5 Cromwell Place to sit for his portrait. The Lavery's organised dinner parties so that the Irish delegation “should meet with Englishmen of importance concerned with the Irish question.” Hazel Lavery reported to Prime Minister Lloyd George that all but Erskine Childers attended.

In his autobiography, ‘The Life of a Painter,’ published in 1940, John Lavery wrote, “By many it was believed that had it not been for Hazel there would have been no Treaty – certainly not at the time it was signed. She had given up on Erskine Childers as impossible to move, but she had overcome Arthur Griffith’s objections. On the night Michael Collins stood firm to the last minute... eventually after hours of persuasion, Hazel prevailed. She took him to Downing Street in her car that last evening, and he gave in.” Present during the Lavery’s attempts to change Collins mind was Moya Llewellyn Davies, wife of the solicitor general to the British Post Office with whom it has been alleged Collins had a relationship. It is further alleged that the relationship if publicised would have led to her divorce and for Collins similar treatment to that suffered by Charles Stuart Parnell.

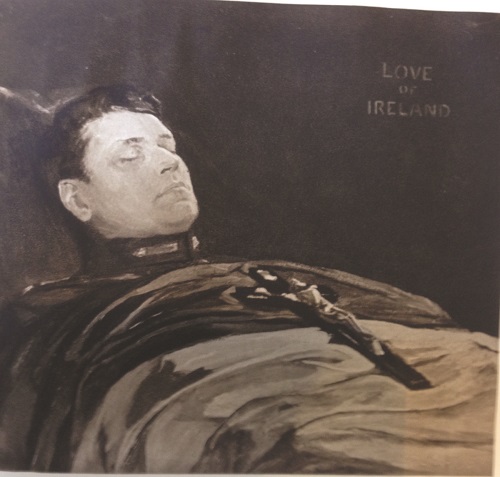

When the Irish delegation returned to Dublin, Lord and Lady Lavery also went over. A dinner party was arranged one night in Kingstown Hotel. Hazel and John attended. Afterwards Hazel brought Collins to meet Horace Plunkett. Her husband did not go. On their way home a dozen shots were poured into the car but no-one was injured. Next day Collins was shot at Béal na Blath. Andy Cope, The Prime Minister’s representative in Ireland made arrangements for Collins body to be brought by sea to Dublin and gave permission for Lavery to paint him in death in the mortuary chapel.

After the death of Collins Hazel Lavery turned her attention to Kevin O’Higgins then in charge of the new Irish government’s “home affairs”. The Lavery’s sought to be the occupants of the Vice-Regal Lodge in Phoenix Park with Sir John as Governor General. The English and O’Higgins were in favour of this. On meeting Lavery, Winston Churchill asked him if he was getting ready for the Vice-Regal. When Kevin O’Higgins was shot dead on his way to mass on 10 July 1927 their hopes were quashed and the post awarded to O’Higgins uncle, Tim Healy. It has been said that Healy had been working for the British since the Invincibles arrests in 1883. Following Healy’s appointment in December 1922 the Cosgrave government softened the blow for Lady Hazel when Cosgrave told her he would put her “next to every Irishman’s heart”. Her portrait would adorn the new Free State £1 note and Sir John would be given the commission of designing it. Seven notes ranging from 10 shillings to £100 were in circulation from 1928 until the 1970s.

It was of little consolation to Lady Lavery who died in 1935, six years before her husband.